On-call systems are often designed with the intention of being rational and structured, yet they are lived through the very human experience of stress, urgency, fatigue, and responsibility. True reliability emerges not only from strong technical systems but from thoughtful escalation design that respects both the service and the people behind it.

Escalation is not merely a chain of reaction, but a choreography of awareness, expertise, and timing. The best teams treat escalation as clarity rather than chaos, and coverage as assurance rather than burden.

Key Takeaways

- Escalation in on-call enables faster resolution by involving the right expertise when complexity exceeds the primary responder’s scope.

- Clearly defined escalation roles prevent confusion and help incidents flow toward resolution instead of bottlenecking at one individual.

- Impact-driven escalation timelines ensure urgency and response speed match the real consequences to users and business stability.

- Reliable alert routing and coverage guarantee that every alert reaches someone able and awake, reducing silent failures and response delays.

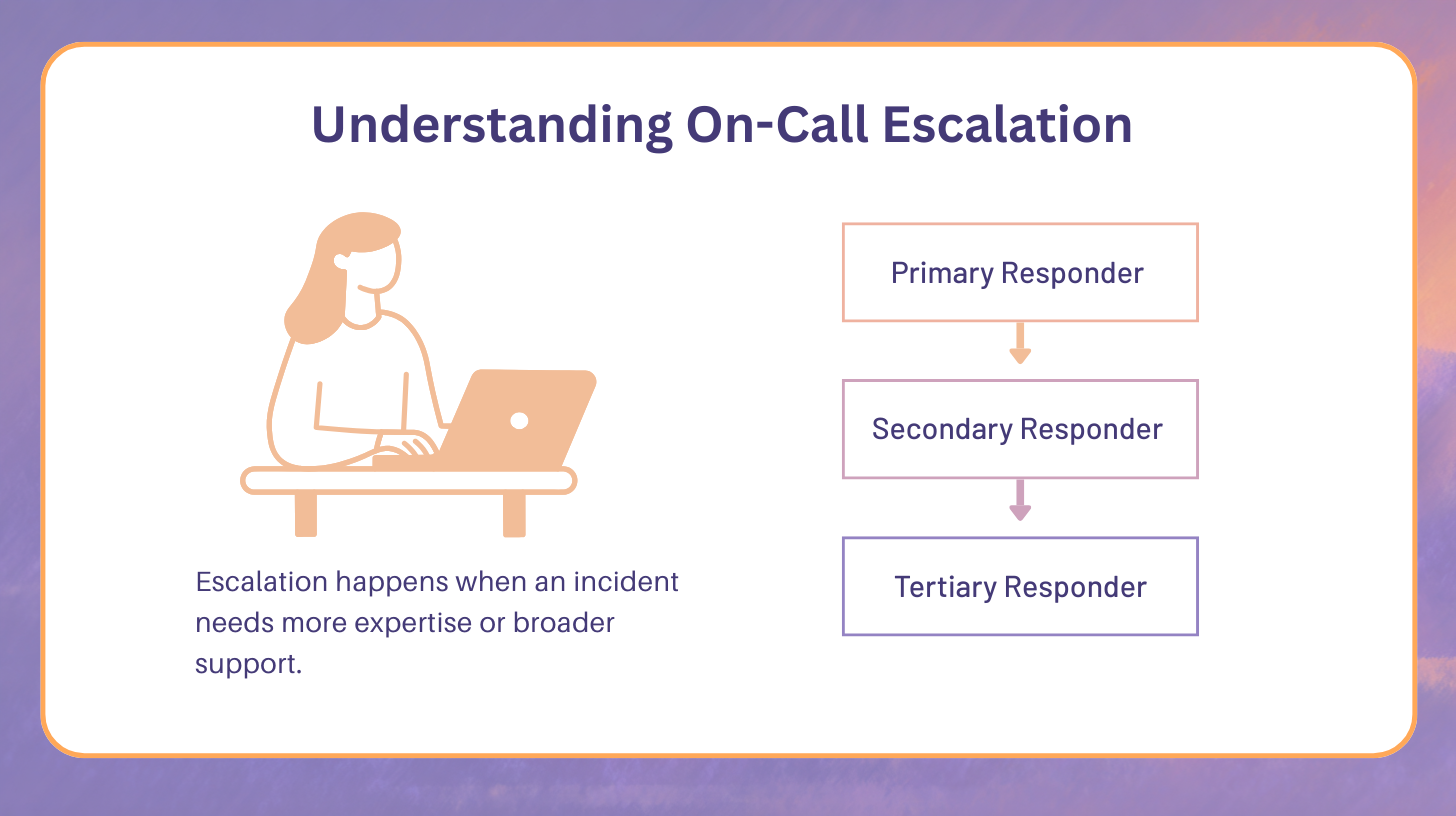

Understanding On-Call Escalation

What escalation means in an incident context

Escalation is not an admission of inadequacy, but a recognition that certain incidents require broader or more specialized attention. When the responder triggers escalation, they are protecting both the system and their own cognitive boundaries. Healthy teams understand that escalation is not about hierarchy or capability, but about optimizing the odds of recovery.

Primary vs Secondary vs Tertiary responders

The first person to receive the alert begins with acknowledgment, initial triage, and quick severity evaluation. They are responsible for deciding whether they can proceed or whether it is time to escalate. If the issue exceeds their scope or becomes ambiguous, escalation begins.

Typical progression looks like this:

- Primary responder: handles acknowledgment, triage, and quick diagnostics

- Secondary responder: provides deeper domain context and service-specific knowledge

- Tertiary responder: brings high-level expertise and strategic decision-making for systemic resolution

This layered system ensures incidents move fluidly toward resolution instead of becoming bottlenecked with a single individual. Each escalation step is not about handing off responsibility, but about adding stronger clarity and capability at the right stage.

Typical escalation timelines and expectations

Escalation timelines should reflect impact instead of arbitrary time blocks. Fast acknowledgment reinforces trust in the system while slow acknowledgment signals risk and uncertainty. Teams that publish expected response thresholds enable psychological safety and keep pressure focused on action rather than fear.

Who Gets the First Alert?

The first alert almost always goes to the primary on-call engineer, whose duty is to acknowledge, triage, and decide whether escalation is needed. When the primary fails to acknowledge due to technical or human limitations, rerouting mechanisms must kick in reliably. Silent failures matter more than noisy ones because they create false confidence that someone is already working the problem.

- Primary duties: immediate triage, acknowledgment, and communication

- Rerouting when primary fails: automated secondary escalation vs manual paging

- Handling silent failures: missed pages, dead batteries, sleep depth, or travel conditions

- Emergency overrides: forcing escalation to a broader responder pool when uncertainty is present

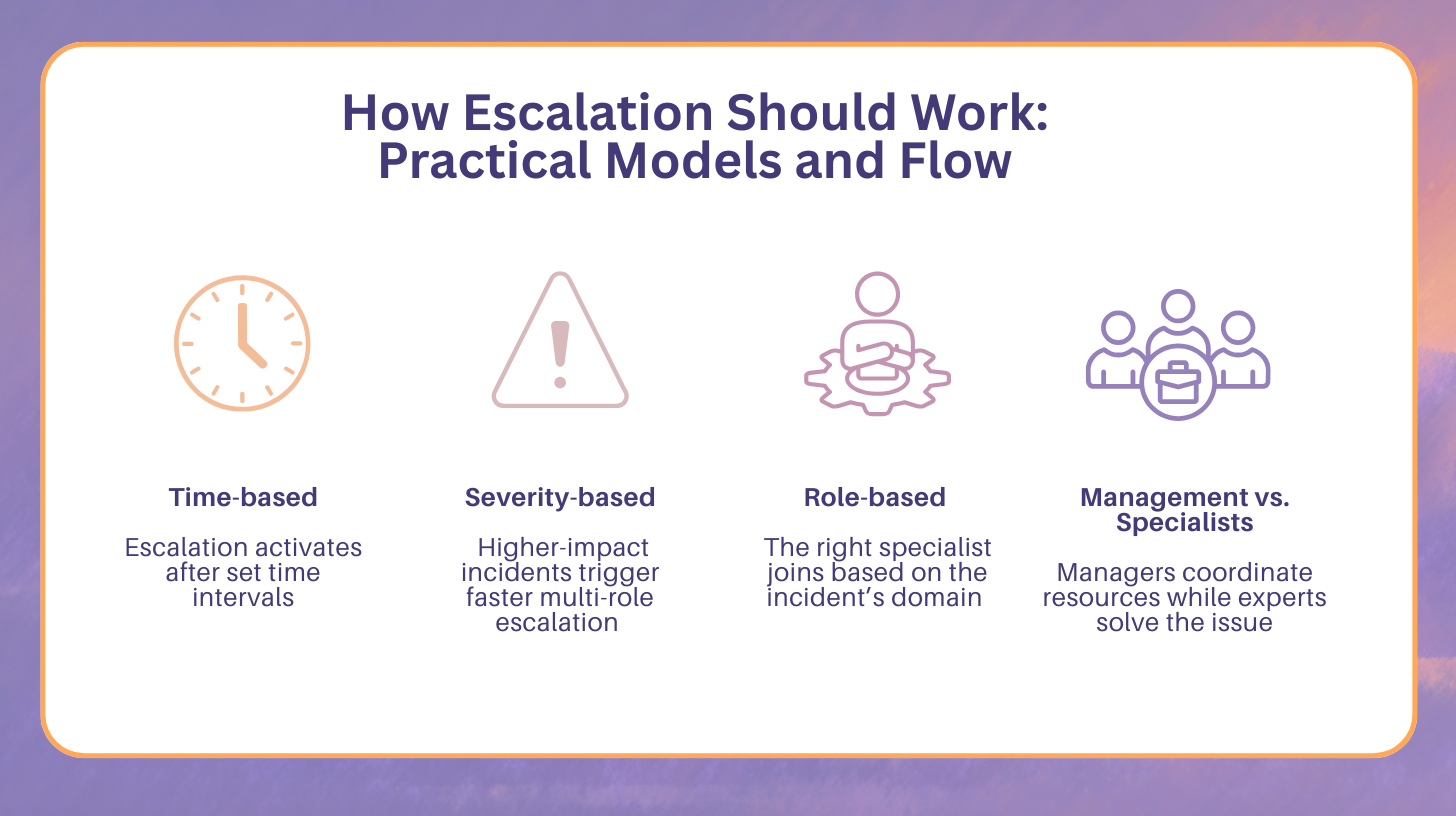

How Escalation Should Work: Practical Models and Flow

Time-based escalation triggers

Time-based triggers use measured delays to reroute when acknowledgment does not occur. This approach is fair because it treats interruptions as bounded, not indefinite. Many teams use tiers of 5, 10, and 15 minutes depending on severity and business impact.

Severity-based escalation

Higher-severity issues require faster escalation and broader peripheral awareness. A SEV-1 might immediately engage multiple roles, while a SEV-3 remains within a single service domain. The key is having severity definitions that are not theoretical but tied directly to measurable consequences like customer experience and data risk.

Role-based escalation

Some incidents are best solved by bringing in the right specialty early instead of pushing the primary to improvise. Database failures often need a DBA, authentication failures require security engineers, and network anomalies call for routing specialists. Escalation becomes sharper and faster when roles are not interchangeable guesses but clearly defined competencies.

When to escalate to management vs when to escalate to specialists

Escalation to management is not for technical debugging but for resource authority and cross-team prioritization. Specialists are engaged to solve, while managers are engaged to coordinate, unblock, and communicate. Knowing which channel to escalate to saves time and lowers emotional load.

Multi-Level Support Structures (L1, L2, L3, L4)

L1: Front-line responder for immediate triage

L1 handles incoming alerts and determines whether the problem is surface-level or deeper. They might not fix the issue but can accurately categorize it. Their role is like a medical triage nurse: rapid judgment and redirection.

L2: Specialist or service owner for deeper troubleshooting

L2 responders understand the architecture and own specific services. They know the internal assumptions that might have been violated. Their work often bridges logs and intuition.

L3: Engineering developers for root-cause debugging

L3 resources are the people who built the system or feature that failed. They can reason about unknown edge-cases because they shaped the logic and structure behind them. Escalation to L3 should not be frequent, but when it happens, it tends to lead to lasting fixes rather than patchwork.

L4: Vendor or external partner escalation

External escalation is for failures in services outside internal control such as cloud providers, CDNs, or authentication providers. These cases require patience and clarity because timelines may no longer be under internal control. Teams that maintain good vendor relationships tend to see faster and more transparent resolutions.

Sequential vs Parallel Escalation: Which Works Better?

The linear escalation model

Linear escalation respects cognitive order, passing issues upwards slowly and methodically. This model is suitable where problems are isolated and stakes are moderate. It prevents crowding and avoids waking two engineers when one will do.

The parallel escalation model

Parallel escalation pulls in multiple support layers simultaneously. It accelerates resolution but risks over-allocating human attention. This model is best for urgent incidents where every minute multiplies cost or customer impact.

When to use each based on severity and urgency

The most efficient teams dynamically switch between escalation modes depending on real-time signals. They do not wait for rules but interpret context. This judgment is learned through exposure rather than policy.

Global Coverage: Ensuring Someone Is Always Awake

Follow-the-sun model

Follow-the-sun rotations take advantage of global time zones. This removes sleep-interrupt incidents and leads to clearer cognitive performance. It works best when system knowledge is distributed evenly worldwide.

Single-geo model

Single-region teams keep tight cultural and communication cohesion. The drawback is sleep interruptions and local fatigue concentration. This approach requires strong alert tuning to avoid burnout.

Hybrid coverage model

Hybrid coverage mixes local primaries with remote backups. It recognizes that not every incident requires deep service familiarity. Some issues just need acknowledgment and redirection toward someone awake.

Hand-off protocols to prevent dropped alerts

Handoffs must be ritualized to prevent uncertainty. Simple checklists often prevent chaos. Whenever a shift turn happens, knowledge should travel with intent, not with assumption.

Dealing with Alert Storms & Multiple Simultaneous Incidents

When multiple alerts strike at once, responders must think like dispatchers rather than mechanics, determining not which alert is loudest but which threatens the most damage. Clear prioritization frameworks prevent emotional decision-making and keep teams aligned with impact-based rather than attention-based triggers. In these moments, communication quality matters as much as technical skill.

- Prioritize by business impact, not by loudness

- Assign alternates to split focus

- Trigger command structure when needed

- Keep communication channels simple and consistent

Escalation Decision Making: When and Why to Escalate

Is escalating necessary or premature

Escalation should happen when uncertainty persists, not only when failure is proven. Waiting too long is more dangerous than escalating too early. Teams learn to normalize caution, not bravado.

How to avoid over-escalation

Over-escalation desensitizes the team and erodes urgency. Asking for help should not mean mobilizing the entire engineering organization. Effective responders escalate with precision.

The emotional side: escalation and psychological safety

People hesitate to escalate when they fear judgment. Teams that encourage vulnerability and openness see faster resolution times. Encouragement is a technical tool, not a cultural nicety.

Recognizing when the responder needs backup

Even the most seasoned engineers reach cognitive saturation. Leaders must proactively detect signs of overload instead of waiting for the responder to verbalize it. Resilience is a shared responsibility.

Tools and Automation for Smarter Escalation

- Pager systems and automated routing reduce ambiguity by ensuring alerts are directed to the right responder without manual intervention.

- Predictive alert scheduling using error history anticipates escalation by analyzing past patterns and involving appropriate expertise early.

- Auto-grouping and noise reduction for alert storms consolidates related alerts so responders can focus on root causes rather than scattered symptoms.

- Incident dashboards and real-time status reporting keep all stakeholders aligned by presenting a unified view of the incident in progress.

Escalation Documentation & Knowledge Sharing

- Documenting escalation reasons and actions preserves decision context so future responders understand not just what was done, but why it was done.

- Building searchable internal knowledge bases centralizes shared learning and prevents teams from solving the same problem repeatedly.

Creating reusable runbooks for common failures gives responders guided paths to resolution and reduces uncertainty during high-pressure incidents.